OSU Extension: Understanding Douglas-fir Decline

Trees on the Edge

An OSU publication written by Max Bennett and Christopher Adlam

Causes of Douglas-fir decline and mortality

Besides the ecological loss, this dieback has broader impacts: when dead trees pile up, they add a lot of extra fuel to forests, which raises wildfire risk. This deadwood contributes to high-severity fires and can slow firefighter response. There’s also the loss of timber income, damaged forest scenery, and increased costs of removing hazard trees – which can exceed $5,000 per acre in some cases.OSU’s recommendations emphasize thinning out dense stands of Douglas-fir, especially in dry areas that see less than 35 inches of rain a year. This can help reduce competition for resources like water and sunlight and ease drought stress on the remaining trees. Land managers are also encouraged to add more drought-resistant trees like pines, oaks, and madrones, especially in high-risk areas with hot, dry, south- and west-facing slopes. Douglas-fir struggles to thrive in these exposed spots in a warming climate – for example, the average summer temperatures in southwest Oregon have steadily risen since 2013, with an expected increase of 4.5–6°F by mid-century.

While there are ways to manage and lessen the impact of the dieback, the harsh reality is that without adequate rainfall or frequent low-intensity fires, which historically kept Douglas-fir populations in check, the species will likely lose ground in its lower-elevation ranges. OSU’s ongoing research into tree health and mortality risk aims to guide landowners in making informed choices for preserving forest health. As conditions continue to change, we may see these lower areas transition more permanently to pine-oak woodlands or open savannas.

By understanding the risks and taking proactive steps now, we can give remaining Douglas-firs a chance to survive, while adapting forest landscapes to be more resilient in the face of ongoing climate change.

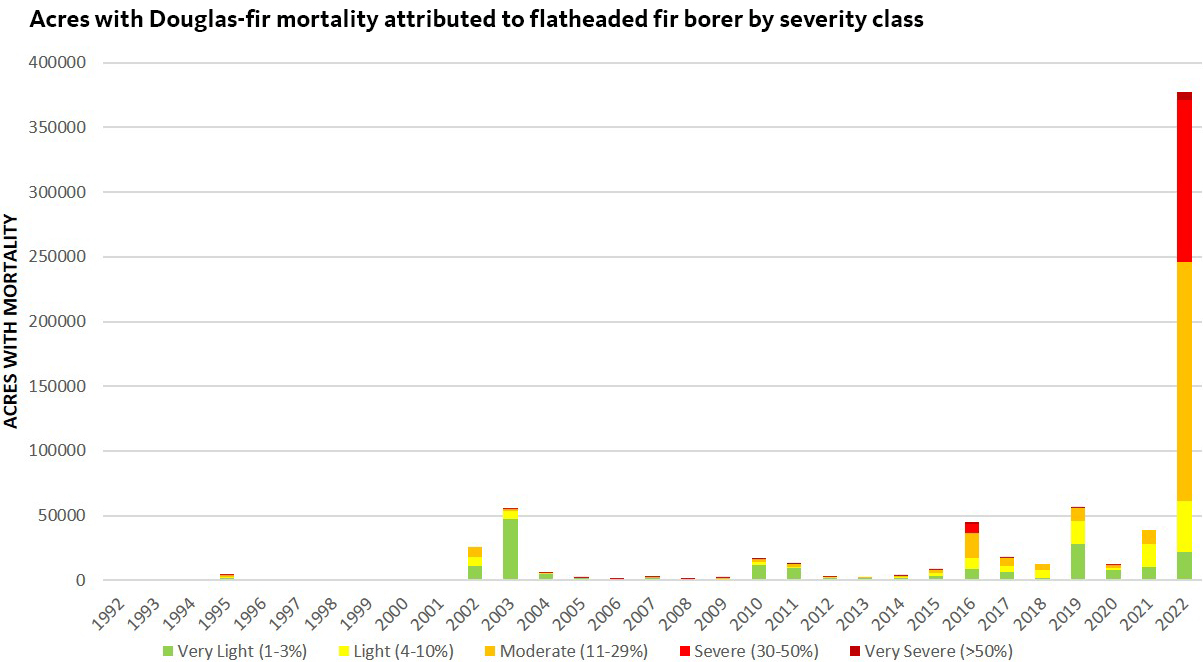

[Figure above: Acres with Douglas-fir mortality attributed to flatheaded fir borer by severity class. The estimate for the number of acres affected is based on aerial sketchmaps that show the general areas Douglas-fir dieback has occurred. It does not necessarily mean that all or even most of the Douglas-fir trees in those areas have been killed. Instead, the estimate represents a mosaic of recently killed trees and living trees. Aerial survey data are most appropriate for monitoring damage and mortality trends at a watershed scale. They do not precisely estimate the number of trees killed or the area affected. Credit: Laura Lowry, U.S. Forest Service.]